De l’Assignifiant

« Pour tout dire, nous ne voyons pas les choses mêmes (…) Nous nous mouvons parmi des généralités et des symboles ».

Henri Bergson, Le rire

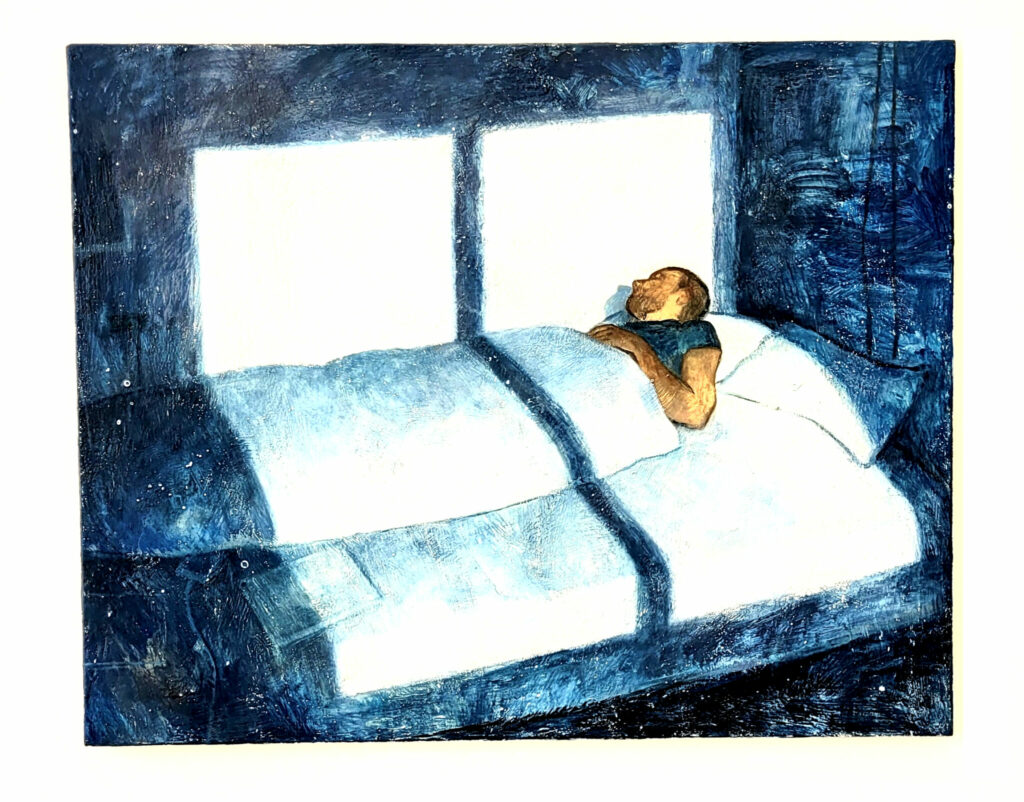

Le banal est englué dans une répétition distrayante et mécanique. Au regard se substitue une myriade de symboles enchevêtrés d’habitudes. Pourtant l’ordinaire recèle d’instants et d’images qui, extraits à la morne inattention quotidienne, offrent des occasions poétiques.

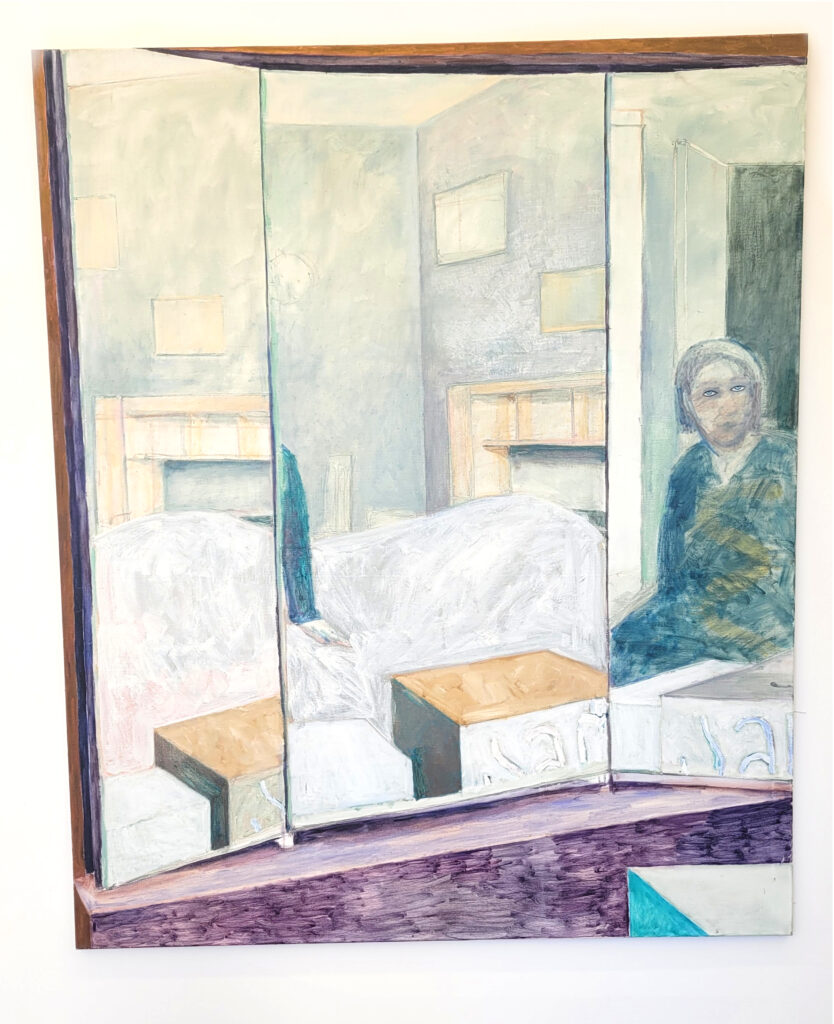

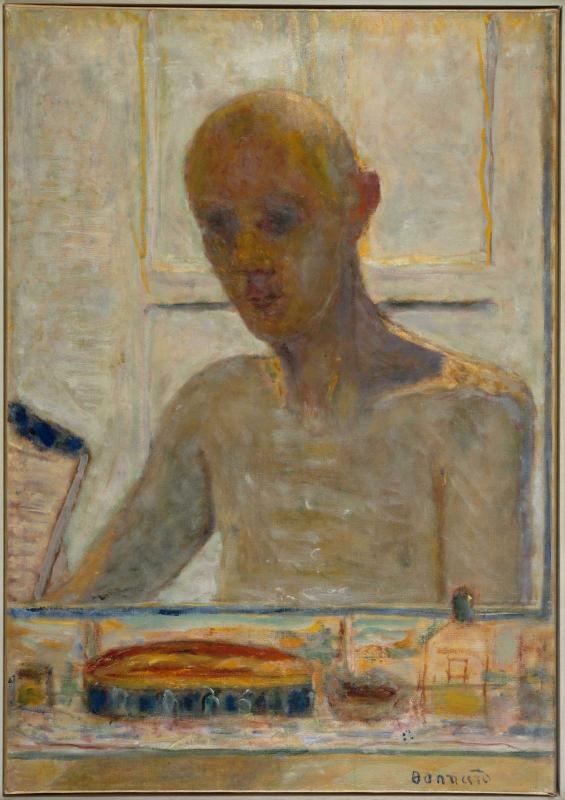

Dans cette constellation assignifiante, le sujet peignant ainsi que son objet peint s’extraient tous deux du signifiant pour tendre vers un assignifiant où la résonance se substitue à la révélation.

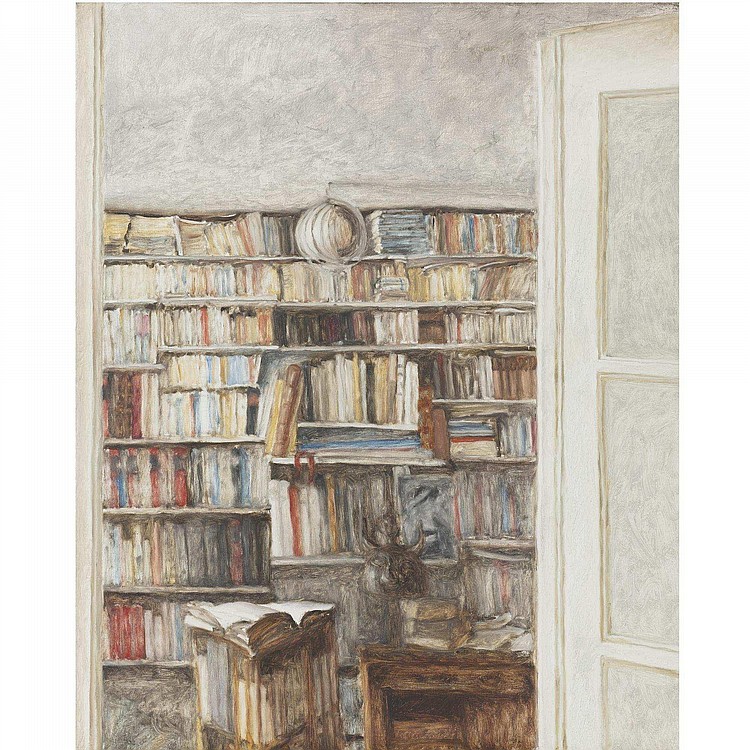

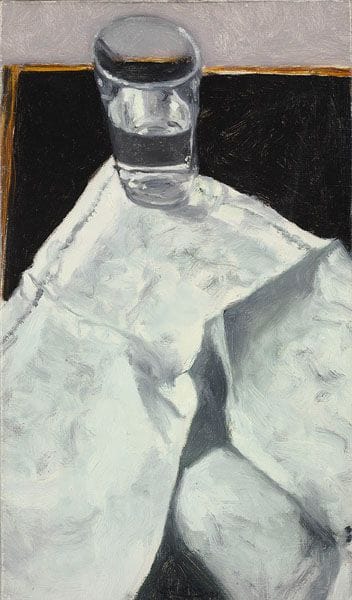

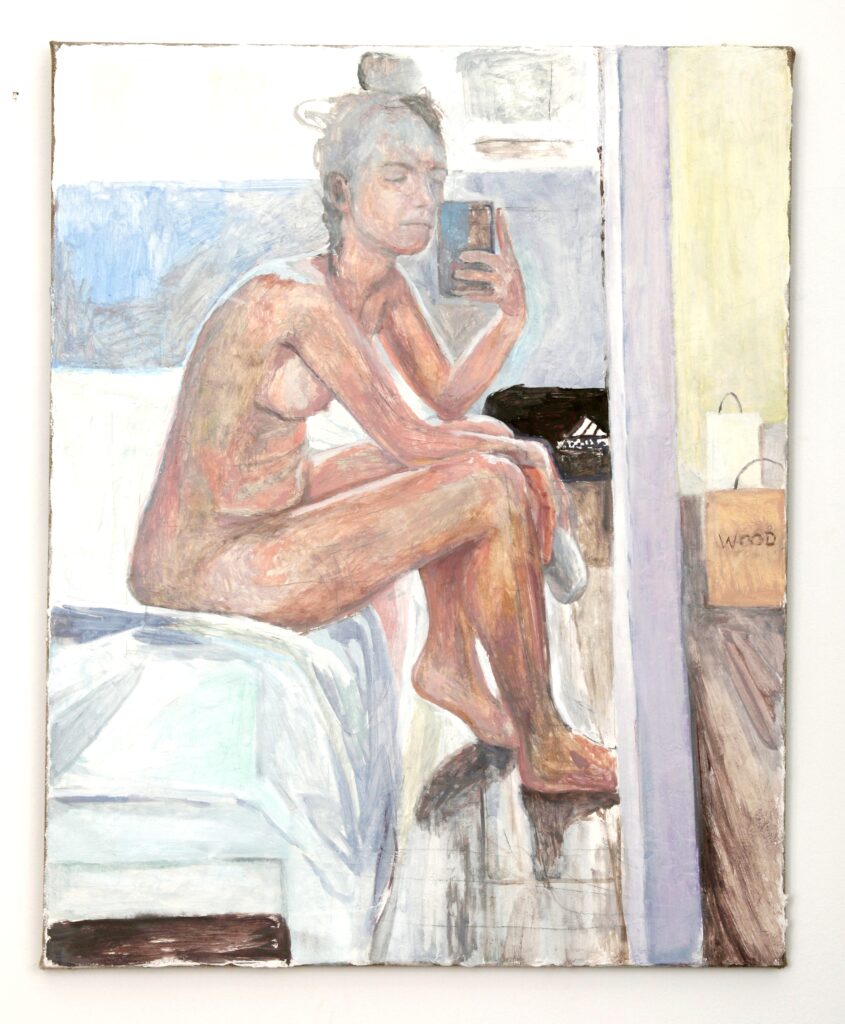

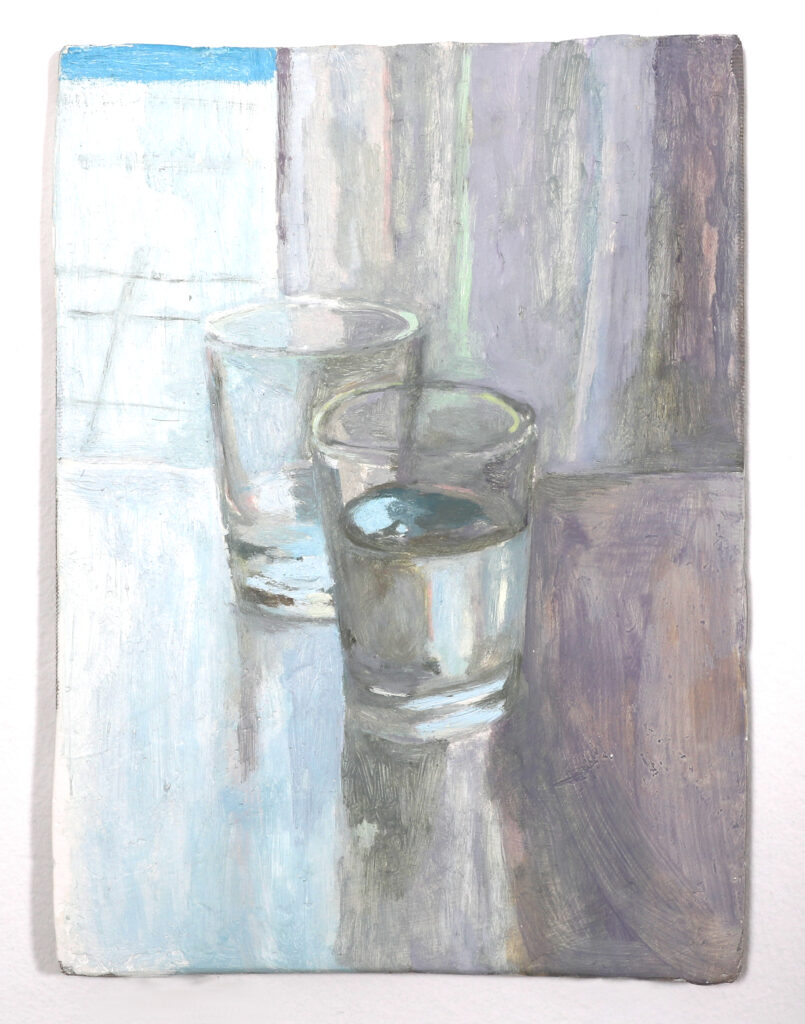

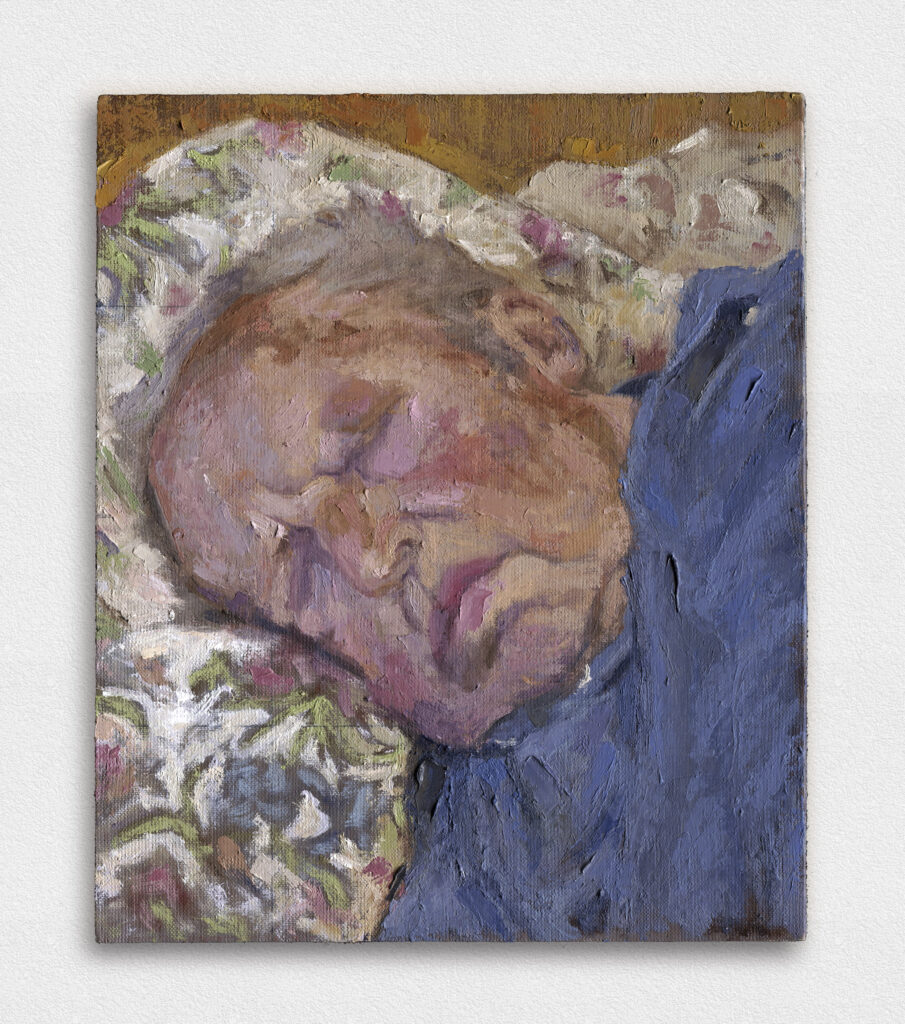

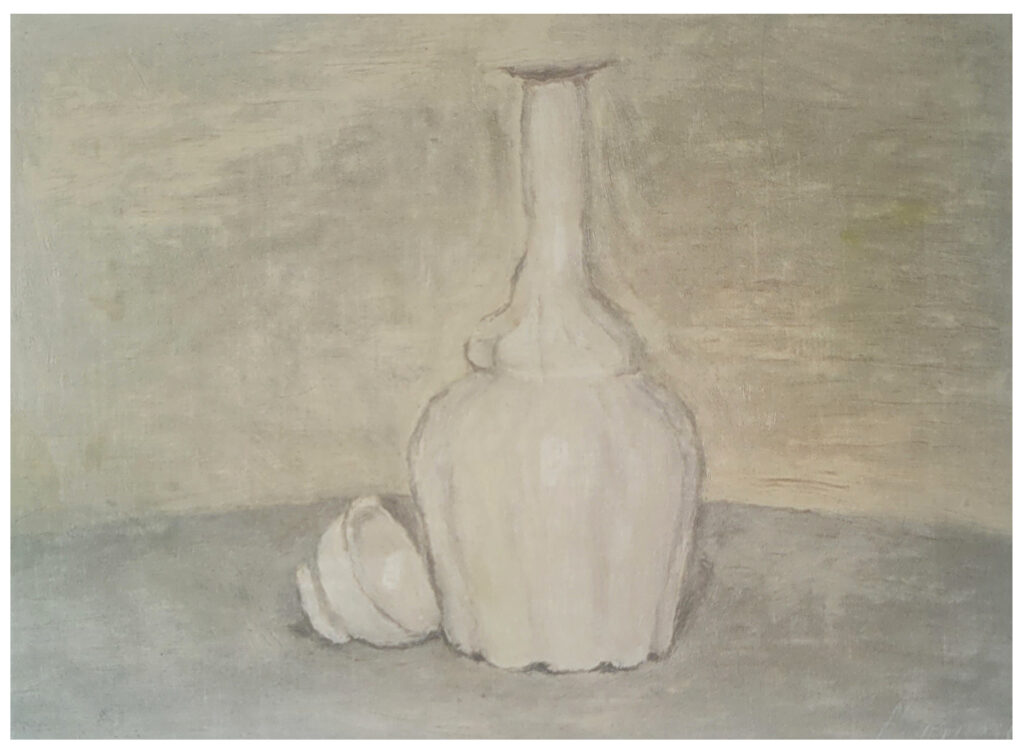

L’œuvre assignifiante n’est ainsi pas descriptive, mais allusive. Nul voile à découvrir, l’objet est devant soi, dans sa modeste simplicité. L’austérité elle-même serait ici presque un effet recherché que la peinture assignifiante récuse ; car cette dernière ne cherche ni à impressionner, ni à choquer ou à politiser ; elle cherche simplement à évoquer une réalité quotidienne, cette vie ordinaire, qui est là, devant soi.

Cette peinture ne révèle rien, ni ne décortique quoi que ce soit : le réel lui est donné tel quel et l’on ne cherche guère à le comprendre et encore moins à le faire comprendre. L’objet n’est d’ailleurs guère observé dans une démarche de maîtrise et de savoir mais simplement regardé. On jette un œil dessus avec un certain égard, cet égard attentif aux petites choses qui nous entourent tant et tellement qu’on les oublie si souvent.

La banalité est cette adhérence des choses à elles-mêmes, là où cette peinture assignifiante décèle en dessillant. Cette decilliation n’est pourtant pas le fruit d’un doigt pointé sur un objet en particulier ou de la mise en exergue d’une quelconque réalité ; la decilliation se fait par la simple évocation d’un moment, aussi anodin soit-il. L’œuvre assignifiante n’est donc pas assignatrice, elle n’indique ni un chemin à prendre ni un sens à donner. Elle relate sobrement un instant, un souvenir, un paysage ou un visage familiers au peintre. Nul sens ou signifiant ne s’en dégage, tout bonnement, une possible résonance.

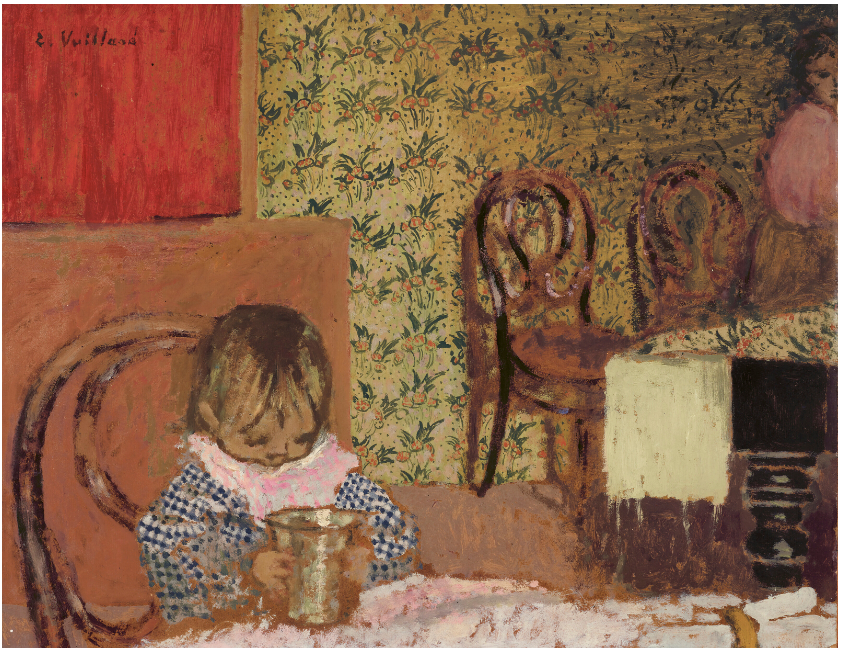

Ainsi, l’intensité n’est pas recherchée mais peut advenir subrepticement. L’œuvre se veut souvent modeste à la fois dans ses objets, dans sa technique, sa palette, et ses compositions. L’effet de manche est refusé car il nous détourne le plus souvent d’un ordinaire qui, à priori ennuyeux, recèle de vibrations poétiques pour qui sait les déceler. La peinture assignifiante ne se détourne donc que rarement de scènes modestes mais aussi vécues ; elle ne cherche pas à divertir, ni d’ailleurs à se confronter, elle tente humblement d’évoquer. Ainsi, le banal enseveli sous l’habitude distrayante se voit ramener au centre, et ainsi transfiguré en objet de peinture. Mais ici, il n’est pas question de transfiguration du banal, la métamorphose d’un objet quotidien en œuvre, mais de banalité du transfigurable, c’est à dire que l’objet peint est cueilli dans le jardin négligé de l’ordinaire. Autrement dit, on ne rabaisse par l’art à un objet banal mais on décèle dans l’épisode banal une résonance poétique ; ainsi on le déterre de la banalité mécanique dans laquelle il était enseveli.

Ramener l’inconnu au connu est une nécessité sociale ; agir sur le monde c’est chercher en permanence à le maîtriser, à le limiter afin qu’il obéisse à nos actions et se rende à nos volontés. Ramener l’inconnu au connu est en quelque sorte la recherche d’une maîtrise, en cela, c’est une nécessité vitale. Cette nécessité a un coût, celui d’obstruer le regard. L’art assignifiant se déprend de cette volonté de maîtrise, se dessaisit de cette volonté de comprendre pour tenter de regarder à nouveau ce qui nous entoure non pour l’altérer mais s’en imprégner. Il y a donc une déprise qui cherche à contourner la méprise due à toute tentative de saisissement. Mais cette déprise n’est pas militante ; elle ne se veut pas solution à un quelconque problème ou issue existentielle ou politique. Elle permet simplement de s’imprégner de toutes ces choses qui tissent l’ordinaire et que l’on oublie si souvent quand on cherche à les utiliser. Il y a conséquemment une forme d’inutilité dans cette démarche assignifiante, puisque, l’instrumentalisation utile contredit l’exploration silencieuse. Cette inutilité est cependant celle du jeu, celle de la nostalgie autant que celle d’un certain humour. La peinture assignifiante renoue ainsi avec une humilité sans déférence, elle est humble en cela que son mouvement principal est le fait de se retirer pour faire place, de s’imprégner de ce que l’ordinaire offre, ne pas chercher à mystifier ou à se distraire mais simplement à regarder, à relater. Elle n’empoigne pas mais explore, tout en laissant les choses venir à soi. Elle n’ambitionne pas de nous sortir de la nécessité mécanique du banal, sauf par touches, sauf par instants.

Ygaël Attali

Of the Assignificant

“To tell the truth, we do not see the things themselves (…) We move among generalities and symbols.

Henri Bergson, Le rire

The banal is caught up in a distracting and mechanical repetition. The gaze is replaced by a myriad of tangled symbols of habits. Yet the ordinary conceals moments and images which, extracted from the dreary daily inattention, offer poetic opportunities.

In this assignifying constellation, the painting subject as well as its painted object both extract themselves from the signifier to tend towards an assignifier where resonance replaces revelation.

The assignifying work is thus not descriptive, but allusive. No veil to discover, the object is in front of you, in its modest simplicity. Austerity itself would be here almost a searched effect that assignifying painting rejects; because the latter does not seek to impress, shock or politicize; it simply seeks to evoke a daily reality, this ordinary life, which is there, in front of you.

This painting does not reveal anything, nor dissects anything: the real is given to it as it is and we hardly try to understand it and even less to make it understood. The object is hardly observed in a process of mastery and knowledge, but simply looked at. We look at it with a certain gaze, this attentive gaze to the little things that surround us so much that we forget them so often.

Banality is this adherence of things to themselves, where this assignifying painting reveals by opening up. This decline is not, however, the result of a finger pointing at a particular object or the highlighting of any reality; the decilliation is done by the simple evocation of a moment, however harmless it may be. The assignifying work is therefore not assigning, it indicates neither a path to take nor a meaning to give. It soberly recounts a moment, a memory, a landscape or a face familiar to the painter. No meaning or signifier emerges from it, quite simply, a possible resonance.

Thus, the intensity is not sought but can occur surreptitiously. The work is often intended to be modest in its objects, in its technique, its palette, and its compositions. The surprise effect is refused because it most often diverts us from an ordinary which, a priori boring, conceals poetic vibrations for those who know how to detect them. Assignifying painting therefore only rarely turns away from modest but also lived scenes; it does not seek to entertain, nor for that matter to confront, it humbly tries to evoke. Thus, the banal buried under the distracting habit is brought back to the center, and thus transfigured into an object of painting. But here, it is not a question of the transfiguration of the banal, the metamorphosis of an everyday object into a work, but of the banality of the transfigurable, that is to say that the painted object is picked from the neglected garden of the ordinary. In other words, we do not reduce art to a banal object but we detect in the banal episode a poetic resonance; thus we unearth it from the mechanical banality in which it was buried.

Bringing the unknown back to the known is a social necessity; to act on the world is to permanently seek to control it, to limit it so that it obeys our actions and surrenders to our will. Bringing the unknown to the known is in a way the search for a mastery, in this it is a vital necessity. This necessity has a cost, that of obstructing the gaze. Assigning art frees itself from this desire for mastery, relinquishes this desire to understand in order to try to look again at what surrounds us, not to alter it but to become impregnated with it. There is therefore a detachment that seeks to circumvent the misunderstanding due to any attempt at seizure. But this abandonment is not militant; it is not meant to be a solution to any existential or political problem or outcome. It simply allows you to soak up all those things that weave the ordinary and that we so often forget when we try to use them. There is consequently a form of uselessness in this assignifying approach, since useful instrumentalization contradicts silent exploration. This uselessness is however that of the game, that of nostalgia as much as that of a certain humor. Assignifying painting thus reconnects with a humility without deference, it is humble in that its main movement is the fact of withdrawing to make room, of soaking up what the ordinary offers, not seeking to mystify or to entertain but simply to watch, to relate. It does not grab but explores, while letting things come to it. It does not aim to get us out of the mechanical necessity of the banal, except by touches, except by moments.

Ygaël Attali